Plywood is made of three or more thin layers of wood bonded together with an adhesive. Each layer of wood, or ply, is usually oriented with its grain running at right angles to the adjacent layer in order to reduce the shrinkage and improve the strength of the finished piece. Most plywood is pressed into large, flat sheets used in building construction. Other plywood pieces may be formed into simple or compound curves for use in furniture, boats, and aircraft.

The use of thin layers of wood as a means of construction dates to approximately 1500 B.C. when Egyptian craftsmen bonded thin pieces of dark ebony wood to the exterior of a cedar casket found in the tomb of King Tut-Ankh-Amon. This technique was later used by the Greeks and Romans to produce fine furniture and other decorative objects. In the 1600s, the art of decorating furniture with thin pieces of wood became known as veneering, and the pieces themselves became known as veneers.

Until the late 1700s, the pieces of veneer were cut entirely by hand. In 1797, Englishman Sir Samuel Bentham applied for patents covering several machines to produce veneers. In his patent applications, he described the concept of laminating several layers of veneer with glue to form a thicker piece—the first description of what we now call plywood.

Despite this development, it took almost another hundred years before laminated veneers found any commercial uses outside of the furniture industry. In about 1890, laminated woods were first used to build doors. As the demand grew, several companies began producing sheets of multiple-ply laminated wood, not only for doors, but also for use in railroad cars, busses, and airplanes. Despite this increased usage, the concept of using "pasted woods," as some craftsmen sarcastically called them, generated a negative image for the product. To counter this image, the laminated wood manufacturers met and finally settled on the term "plywood" to describe the new material.

In 1928, the first standard-sized 4 ft by 8 ft (1.2 m by 2.4 m) plywood sheets were introduced in the United States for use as a general building material. In the following decades, improved adhesives and new methods of production allowed plywood to be used for a wide variety of applications. Today, plywood has replaced cut lumber for many construction purposes, and plywood manufacturing has become a multi-billion dollar, worldwide industry.

The outer layers of plywood are known respectively as the face and the back. The face is the surface that is to be used or seen, while the back remains unused or hidden. The center layer is known as the core. In plywoods with five or more plies, the inter-mediate layers are known as the crossbands.

Plywood may be made from hardwoods, softwoods, or a combination of the two. Some common hardwoods include ash, maple, mahogany, oak, and teak. The most common softwood used to make plywood in the United States is Douglas fir, although several varieties of pine, cedar, spruce, and redwood are also used.

Composite plywood has a core made of particleboard or solid lumber pieces joined edge to edge. It is finished with a plywood veneer face and back. Composite plywood is used where very thick sheets are needed.

The type of adhesive used to bond the layers of wood together depends on the specific application for the finished plywood. Softwood plywood sheets designed for installation on the exterior of a structure usually use a phenol-formaldehyde resin as an adhesive because of its excellent strength and resistance to moisture. Softwood plywood sheets designed for installation on the interior of a structure may use a blood protein or a soybean protein adhesive, although most softwood interior sheets are now made with the same phenol-formaldehyde resin used for exterior sheets. Hardwood plywood used for interior applications and in the construction of furniture usually is made with a urea-formaldehyde resin.

Some applications require plywood sheets that have a thin layer of plastic, metal, or resin-impregnated paper or fabric bonded to either the face or back (or both) to give the outer surface additional resistance to moisture and abrasion or to improve its paint-holding properties. Such plywood is called overlaid plywood and is commonly used in the construction, transportation, and agricultural industries.

Other plywood sheets may be coated with a liquid stain to give the surfaces a finished appearance, or may be treated with various chemicals to improve the plywood's flame resistance or resistance to decay.

There are two broad classes of plywood, each with its own grading system.

One class is known as construction and industrial. Plywoods in this class are used primarily for their strength and are rated by their exposure capability and the grade of veneer used on the face and back. Exposure capability may be interior or exterior, depending on the type of glue. Veneer grades may be N, A, B, C, or D. N grade has very few surface defects, while D grade may have numerous knots and splits. For example, plywood used for subflooring in a house is rated "Interior C-D". This means it has a C face with a D back, and the glue is suitable for use in protected locations. The inner plies of all construction and industrial plywood are made from grade C or D veneer, no matter what the rating.

The other class of plywood is known as hardwood and decorative. Plywoods in this class are used primarily for their appearance and are graded in descending order of resistance to moisture as Technical (Exterior), Type I (Exterior), Type II (Interior), and Type III (Interior). Their face veneers are virtually free of defects.

Sizes

Plywood sheets range in thickness from. 06 in (1.6 mm) to 3.0 in (76 mm). The most common thicknesses are in the 0.25 in (6.4 mm) to 0.75 in (19.0 mm) range. Although the core, the crossbands, and the face and back of a sheet of plywood may be made of different thickness veneers, the thickness of each must balance around the center. For example, the face and back must be of equal thickness. Likewise the top and bottom crossbands must be equal.

The most common size for plywood sheets used in building construction is 4 ft (1.2 m) wide by 8 ft (2.4 m) long. Other common widths are 3 ft (0.9 m) and 5 ft (1.5 m). Lengths vary from 8 ft (2.4 m) to 12 ft (3.6 m) in 1 ft (0.3 m) increments. Special applications like boat building may require larger sheets.

The trees used to make plywood are generally smaller in diameter than those used to make lumber. In most cases, they have been planted and grown in areas owned by the plywood company. These areas are carefully managed to maximize tree growth and minimize damage from insects or fire.

Here is a typical sequence of operations for processing trees into standard 4 ft by 8 ft (1.2 m by 2.4 m) plywood sheets:

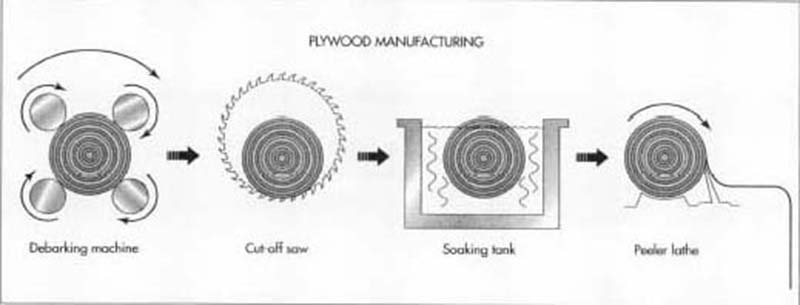

The logs are first debarked and then cut into peeler blocks. In order to cut the blocks into strips of veneer, they are first soaked and then peeled into strips.

1 Selected trees in an area are marked as being ready to be cut down, or felled. The felling may be done with gasoline-powered chain saws or with large hydraulic shears mounted on the front of wheeled vehicles called fellers. The limbs are removed from the fallen trees with chain saws.

2 The trimmed tree trunks, or logs, are dragged to a loading area by wheeled vehicles called skidders. The logs are cut to length and are loaded on trucks for the trip to the plywood mill, where they are stacked in long piles known as log decks.

3 As logs are needed, they are picked up from the log decks by rubber-tired loaders and placed on a chain conveyor that brings them to the debarking machine. This machine removes the bark, either with sharp-toothed grinding wheels or with jets of high-pressure water, while the log is slowly rotated about its long axis.

4 The debarked logs are carried into the mill on a chain conveyor where a huge circular saw cuts them into sections about 8 ft-4 in (2.5 m) to 8 ft-6 in (2.6 m) long, suitable for making standard 8 ft (2.4 m) long sheets. These log sections are known as peeler blocks.

5 Before the veneer can be cut, the peeler blocks must be heated and soaked to soften the wood. The blocks may be steamed or immersed in hot water. This process takes 12-40 hours depending on the type of wood, the diameter of the block, and other factors.

6 The heated peeler blocks are then transported to the peeler lathe, where they are automatically aligned and fed into the lathe one at a time. As the lathe rotates the block rapidly about its long axis, a full-length knife blade peels a continuous sheet of veneer from the surface of the spinning block at a rate of 300-800 ft/min (90-240 m/min). When the diameter of the block is reduced to about 3-4 in (230-305 mm), the remaining piece of wood, known as the peeler core, is ejected from the lathe and a new peeler block is fed into place.

7 The long sheet of veneer emerging from / the peeler lathe may be processed immediately, or it may be stored in long, multiple-level trays or wound onto rolls. In any case, the next process involves cutting the veneer into usable widths, usually about 4 ft-6 in (1.4 m), for making standard 4 ft (1.2 m) wide plywood sheets. At the same time, optical scanners look for sections with unacceptable defects, and these are clipped out, leaving less than standard width pieces of veneer.

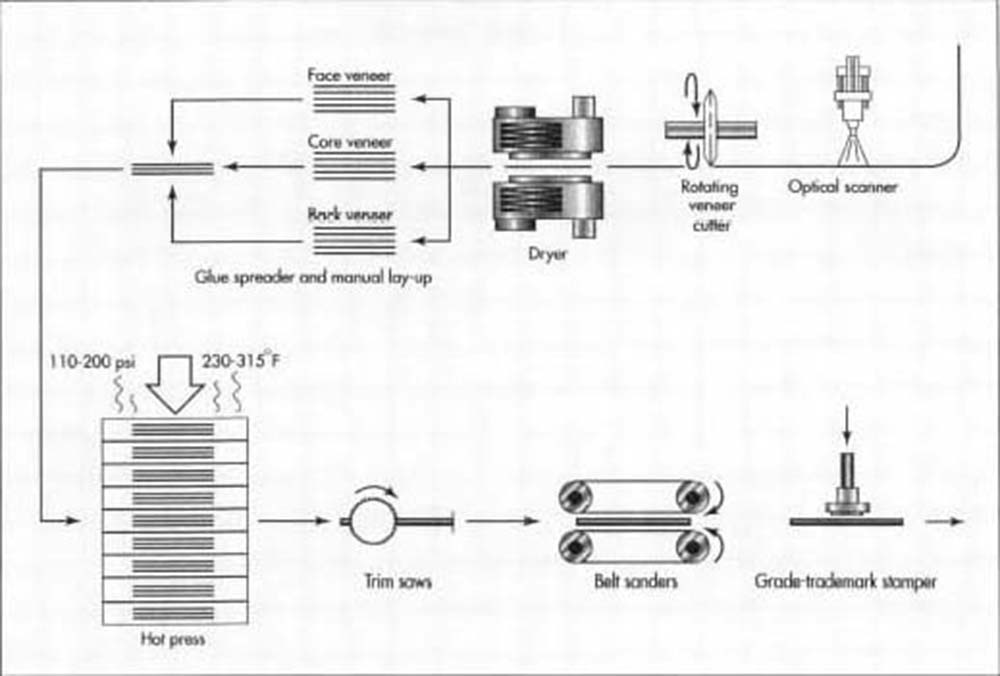

The wet strips of veneer are wound into a roll, while an optical scanner detects any unacceptable defects in the wood. Once dried the veneer is graded and stacked. Selected sections of veneer are glued together. A hot press is used to seal the veneer into one solid piece of plywood, which will be trimmed and sanded before being stamped with its appropriate grade.

8 The sections of veneer are then sorted and stacked according to grade. This may be done manually, or it may be done automatically using optical scanners.

9 The sorted sections are fed into a dryer to reduce their moisture content and allow them to shrink before they are glued together. Most plywood mills use a mechanical dryer in which the pieces move continuously through a heated chamber. In some dryers, jets of high-velocity, heated air are blown across the surface of the pieces to speed the drying process.

10 As the sections of veneer emerge from the dryer, they are stacked according to grade. Underwidth sections have additional veneer spliced on with tape or glue to make pieces suitable for use in the interior layers where appearance and strength are less important.

11 Those sections of veneer that will be installed crossways—the core in three-ply sheets, or the crossbands in five-ply sheets—are cut into lengths of about 4 ft-3 in (1.3 m).

12 When the appropriate sections of veneer are assembled for a particular run of plywood, the process of laying up and gluing the pieces together begins. This may be done manually or semi-automatically with machines. In the simplest case of three-ply sheets, the back veneer is laid flat and is run through a glue spreader, which applies a layer of glue to the upper surface. The short sections of core veneer are then laid crossways on top of the glued back, and the whole sheet is run through the glue spreader a second time. Finally, the face veneer is laid on top of the glued core, and the sheet is stacked with other sheets waiting to go into the press.

13 The glued sheets are loaded into a multiple-opening hot press. presses can handle 20-40 sheets at a time, with each sheet loaded in a separate slot. When all the sheets are loaded, the press squeezes them together under a pressure of about 110-200 psi (7.6-13.8 bar), while at the same time heating them to a temperature of about 230-315° F (109.9-157.2° C). The pressure assures good contact between the layers of veneer, and the heat causes the glue to cure properly for maximum strength. After a period of 2-7 minutes, the press is opened and the sheets are unloaded.

14 The rough sheets then pass through a set of saws, which trim them to their final width and length. Higher grade sheets pass through a set of 4 ft (1.2 m) wide belt sanders, which sand both the face and back. Intermediate grade sheets are manually spot sanded to clean up rough areas. Some sheets are run through a set of circular saw blades, which cut shallow grooves in the face to give the plywood a textured appearance. After a final inspection, any remaining defects are repaired.

15 The finished sheets are stamped with a grade-trademark that gives the buyer information about the exposure rating, grade, mill number, and other factors. Sheets of the same grade-trademark are strapped together in stacks and moved to the warehouse to await shipment.

Just as with lumber, there is no such thing as a perfect piece of plywood. All pieces of plywood have a certain amount of defects. The number and location of these defects determines the plywood grade. Standards for construction and industrial plywoods are defined by Product Standard PS1 prepared by the National Bureau of Standards and the American Plywood Association. Standards for hardwood and decorative plywoods are defined by ANSIIHPMA HP prepared by the American National Standards Institute and the Hardwood Plywood Manufacturers' Association. These standards not only establish the grading systems for plywood, but also specify construction, performance, and application criteria.

Even though plywood makes fairly efficient use of trees—essentially taking them apart and putting them back together in a stronger, more usable configuration—there is still considerable waste inherent in the manufacturing process. In most cases, only about 50-75% of the usable volume of wood in a tree is converted into plywood. To improve this figure, several new products are under development.

One new product is called oriented strand board, which is made by shredding the entire log into strands, rather than peeling a veneer from the log and discarding the core. The strands are mixed with an adhesive and compressed into layers with the grain running in one direction. These compressed layers are then oriented at right angles to each other, like plywood, and are bonded together. Oriented strand board is as strong as plywood and costs slightly less.

Post time: Aug-10-2021